Stimulated by Cathenaut et al 2023.[1]

STP – short term plasticity

key to acronyms

DH – dorsal horn (the sensory horn of the spinal cord)

EA – electroacupuncture

Circa – approximately (sometimes shortened to c)

TRPV1 – transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1

GABA – gamma-aminobutyric acid

NMDA – N-methyl D-aspartate (a type of glutamate receptor)

L-type Ca2+ – a voltage dependent calcium channel with long lasting (L-type) activation

I have always been drawn to the basic science data on nerves, nerve function, and neural connections, because this data allows us to make some hypothetical leaps into clinical practice and should stop us making some others.

When I was first learning about the neurophysiological mechanisms of acupuncture, the DH and its connections were clearly a key area of interest. Unfortunately, the human DH is not easy to visualise in vivo, so we had to make simplified assumptions from a combination of human neuroanatomical studies and experimental studies on a variety of animal models.

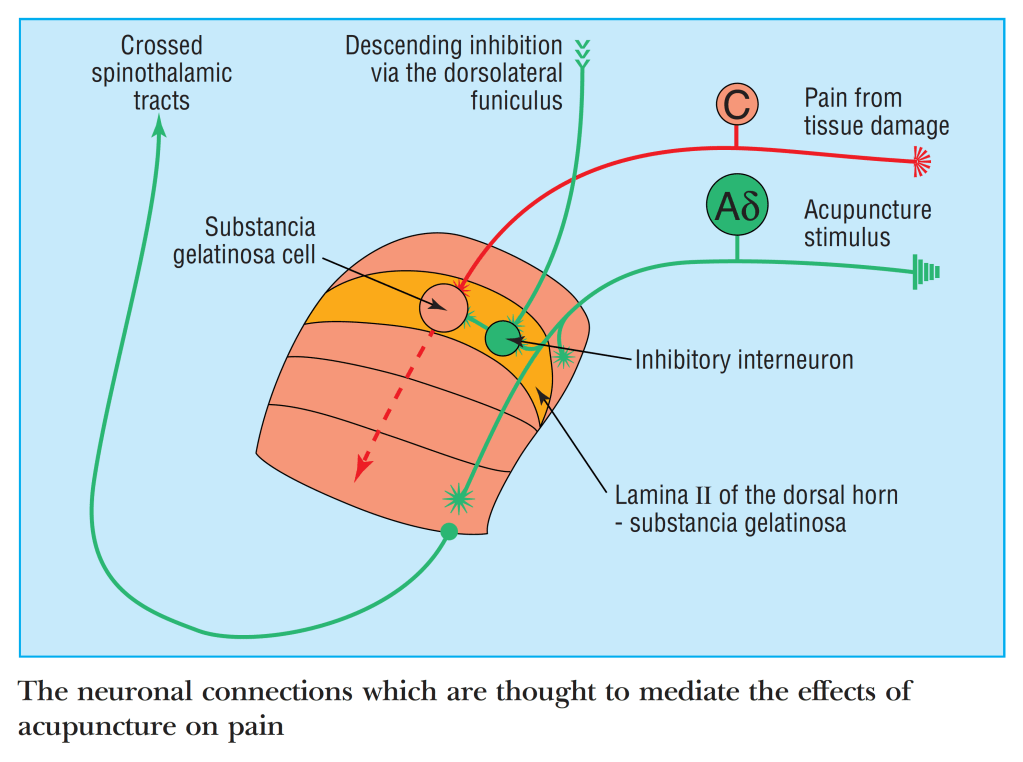

The graphic above is a very simplistic illustration of spinal modulation of C fibre nociception by Aδ fibre stimulation derived from an acupuncture stimulus. I was happy enough with this 25 years ago, since acupuncture often seemed to work better the closer you got the needle to the problem area. Doubts started to creep in when new information did not quite fit this simple model. For example, I learned that acupuncture often stimulates the same C fibres we were happily inhibiting in this graphic. Then there was Thomas (Lundeberg), who kept mentioning that the analgesic effect in humans requires a long loop involving the brainstem, and that spinal connections alone were not enough. I looked for more detailed descriptions of spinal connections to support my hunch that proximity of the needle mattered, but there was nothing to find beyond David Bowsher’s excellent chapter in the first big textbook by Filshie and White.[3]

This is why papers like this draw me in. Will there be confirmation of our contemporary ideas or not? Well, this paper looks at short term changes in neural activity and we, of course, are more interested in longer term responses, but as the authors of this paper recognise, some short-term phenomena (eg wind up) are likely to be similar mechanistically to related longer term ones (central sensitisation). If the connections exist for certain short-term changes, then the same connections could be responsible for mediating longer term effects.

The other interesting aspect to this paper is the reporting of discharge frequencies in C and Aδ nerve fibres. Their interest is in the information that can be coded into the different frequencies, but our interest is also in what is likely to be the optimal frequencies to apply when stimulating deep somatic nerves as part of EA treatment.

So, what did I learn from this paper? Nociceptive C fibres can discharge at up to 2Hz during non-noxious stimulation, but this activity is not associated with nociceptive behavioural responses. Nociceptive stimuli result in initial C fibre discharge frequencies of over 50Hz, but these frequencies rapidly diminish such that the average over the first second is circa 5–10Hz, and subsequently this drops to under 2Hz. At each stage the intensity of the stimulus corelates positively with the discharge frequency, that is the frequency encodes information about intensity.

Αδ nociceptive fibres have a higher discharge frequency initially (typically over 100Hz) but they do not all adapt as rapidly as C fibres, so the average discharge rate over the first second is 5–50Hz. Subsequently, the typical discharge rate for Aδ fibres is circa 5Hz. Interestingly, only the initial discharge rate encodes information on intensity and not the subsequent plateau rate.

In C fibres, continuous stimulation results in a slowing of the action potential velocity (activity dependent slowing) to around one third of the initial velocity. This occurs after about 20s at 20Hz and 150s at 2Hz.

So, what does this mean to us in acupuncture? If most of the effects we seek are derived from stimulation of Aδ or C fibres, there is little point trying to stimulate them above 5Hz, and 1–2Hz may be more optimal in situations where effects are principally mediated via C fibres.

Moving on to the DH itself… Most neurons in lamina II (the substancia gelatinosa) receive monosynaptic or polysynaptic input from C fibres, of which, 30–80% express TRPV1. Also, more than 20% of lamina II neurons using GABA (hence inhibitory) are contacted by Aδ fibres.

Lamina II neurons come in at least 4 varieties.[4] Islet cells are exclusively inhibitory and have extensive intralaminar dendritic arborisation patterns up and down (rostrocaudal), extending to adjacent segments. Central cells follow a similar but less extensive pattern of dendritic connections and come in either inhibitory or excitatory varieties. Vertical cells, in spite of their name, have extensive translaminar dendritic arborisation patterns, principally connecting within the segment and the majority are excitatory. Finally, the radial cells have the least extensive dendritic arborisation and are also predominantly excitatory.

This anatomical pattern suggests within segment excitation from peripheral inputs but perisegmental inhibition from the same or similar nociceptive inputs.

Wind-up occurs principally in the deep DH (laminae V–VI) and results from relatively low discharge rates (0.33–5Hz) in C fibres. Other types of sensory afferents are not generally associated with wind-up. In the deep DH this process is mediated by NMDA receptors and L-type Ca2+ channels and can amplify signal frequency by 10- to 20-fold. Interestingly, NMDA receptors in lamina II result in inhibition of the deep DH rather than wind-up. Some amplification (2- to 3-fold) can occur in the superficial DH (reduced wind-up), but this is not mediated by NMDA receptors and can reset rapidly following a loss of just one or two discharges from the periphery. This is called wind-up reset.

Well, it is all very interesting, and I have learned quite a lot, but I’ve been on it most of the weekend and I don’t really have much useful to tell clinicians, apart from the fact that the more we discover, the ever more complex it gets. I will share some of that complexity in graphical form at the blog webinar on Wednesday.

References

1 Cathenaut L, Schlichter R, Hugel S. Short-term plasticity in the spinal nociceptive system. Pain Published Online First: 11 August 2023. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002999

2 Vickers A, Zollman C. ABC of complementary medicine. Acupuncture. BMJ 1999;319:973–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7215.973

3 Bowsher D. Mechanisms of acupuncture. In: Filshie J, White A, eds. Medical Acupuncture – A Western Scientific Approach. Churchill Livingstone 1998. 69–82.

4 Braz J, Solorzano C, Wang X, et al. Transmitting pain and itch messages: a contemporary view of the spinal cord circuits that generate gate control. Neuron 2014;82:522–36. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.018

You must be logged in to post a comment.